If you’re looking for a hearty, filling, and soul-warming meal, you’ve just found it. I want to share with you one of my favorite dishes—red beans and rice.

I grew up loving this recipe because it’s simple, budget-friendly, and loaded with flavor. I’m excited because I know once you try it, you’ll love it too. Let’s jump in.

Why Red Beans and Rice is So Special

This dish is not just food—it’s comfort. Red beans and rice is a classic in Southern and Creole cooking. The beans are creamy, the spices are bold, and the rice ties everything together.

It’s filling, but also healthy and packed with protein. The best part? You don’t need fancy ingredients. Just basics from your pantry.

Ingredients You’ll Need

Here’s what you need to get started:

- Red beans (dried or canned, depending on your time)

- Rice (white rice works best, but you can use brown rice too)

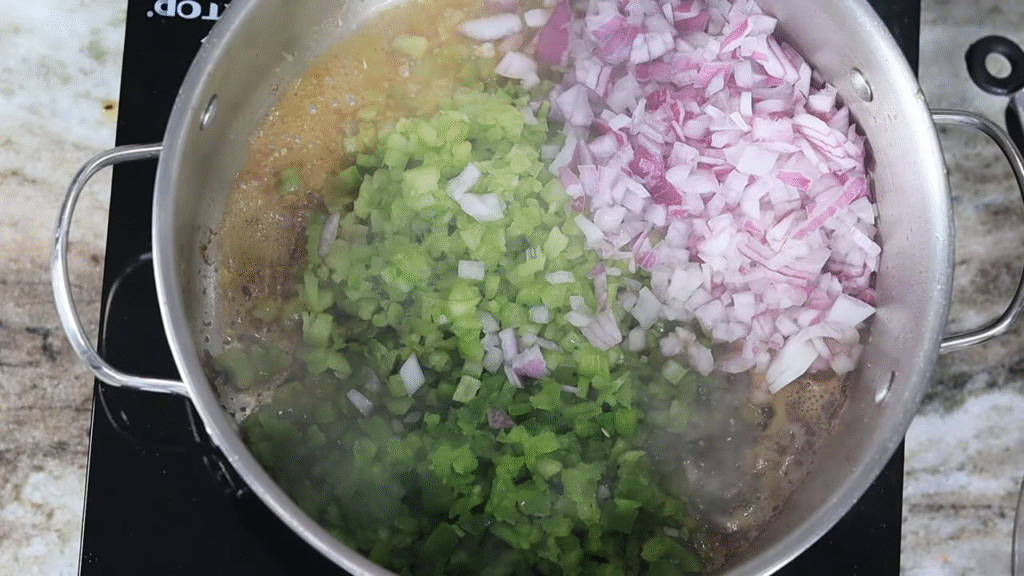

- Onion, celery, bell pepper (the “holy trinity” of flavor)

- Garlic (because garlic makes everything better)

- Smoked sausage or ham (optional but adds so much flavor)

- Bay leaf, thyme, paprika, black pepper, and cayenne (for that kick of spice)

- Chicken broth or water

That’s it! Nothing fancy. You probably have most of these at home right now.

Step-by-Step: How to Make Red Beans and Rice

1. Soak or Prep the Beans

If you’re using dried beans, soak them overnight to soften them. If you forgot, don’t worry—you can use the quick-boil method or just go with canned beans.

2. Cook the Veggies

Chop your onion, celery, and bell pepper. Sauté them in a big pot with a little oil until soft. This step builds the flavor base.

3. Add Meat and Spices

Throw in sliced sausage or ham if you’re using it. Let it brown a bit. Then add garlic, thyme, bay leaf, paprika, pepper, and cayenne. The smell right here is amazing.

4. Add Beans and Broth

Pour in your beans and enough broth (or water) to cover them. Let it simmer low and slow until the beans are soft and creamy. This can take about 1–1.5 hours if using dried beans, or 30 minutes if using canned.

5. Make the Rice

While the beans cook, make your rice on the side. Fluffy white rice works perfectly.

6. Put It Together

Serve a scoop of rice in a bowl and pour those creamy beans right on top. Garnish with a little parsley or green onions if you like.

Tips to Make It Perfect

- Low and slow cooking makes beans creamy. Don’t rush it.

- If it’s too thick, add a splash of broth.

- If it’s too thin, mash a few beans with a spoon to thicken it.

- Adjust the spice level—more cayenne for heat, less if you like it mild.

Why You’ll Love This Recipe

It’s simple, filling, and can feed a crowd without costing much. It tastes even better the next day, which makes it perfect for meal prep. Plus, it’s one of those dishes that feels like a warm hug in a bowl.

FAQs About Red Beans and Rice

Q: Can I make this vegetarian?

Yes! Just skip the sausage or ham and use vegetable broth. The beans and spices bring plenty of flavor.

Q: Do I have to soak the beans?

If you’re using dried beans, soaking helps them cook faster and softer. But you can also use canned beans if you’re short on time.

Q: Can I freeze red beans and rice?

Absolutely. Store in airtight containers and freeze for up to 3 months. Just reheat and enjoy.

Q: What’s the best rice to use?

Long-grain white rice is traditional, but brown rice or even jasmine rice works fine.

Q: How spicy is it?

It’s up to you. You control the cayenne and paprika. Start mild—you can always add more heat later.